Designing effective flood warning systems in Scotland

Published on 2 November 2011 in Climate, water and energy

Introduction

Water is a key resource for Scotland, but when it causes flooding it can result in serious damage and harm. Furthermore, climate change is increasing flood risk in some parts of Scotland. The Flood Risk Management (Scotland) Act came into force on 26 November 2009 and transposes the EC Floods Directive (2007) into national law. Through this Act, the Scottish Government aims to promote streamlined and sustainable flood risk management. It places a duty on the Scottish Government, SEPA, Scottish Water and local authorities to better co-ordinate the assessment and management of flood risk.

The risks from flooding can never be completely eliminated but the harm caused by floods can be greatly reduced or mitigated by effective flood warning systems. However, past experience in Scotland and other countries shows that in times of flooding, many people are not prepared or do not react appropriately. Therefore, this report explores what issues affect communications about flooding and flood risks, and how communications can be improved to produce intended responses from the public.

Key Points

- Flood warnings and communications are generally valued by the public at risk. However, not all those at risk realise that they are. Furthermore, awareness and understanding can be low, or different to that intended. As a result, there is often low preparedness and/or uncertainty about how to react to warnings.

- Perceptions of trustworthiness and reliability of the sources of messages (often influenced by past experiences) can have strong influences on how messages are processed and acted on. Emergency services or community groups can be more trusted than local authorities or SEPA, though they do not have a formal role in flood communications.

- Jargon and terminology associated with floods and risk is often not understood, or misunderstood. Even the difference between ‘Flood Alerts’ and ‘Flood Warnings’ can be confusing.

- New technologies can be useful. SEPA’s website on flooding, and automated messages from Floodline were very often popular where known, but many were not aware of this (question asked in winter 2010).

- Personalised information and personal contact can be popular for providing advice on preparation and how warning systems work. This can also help to reach those unaware they are at risk.

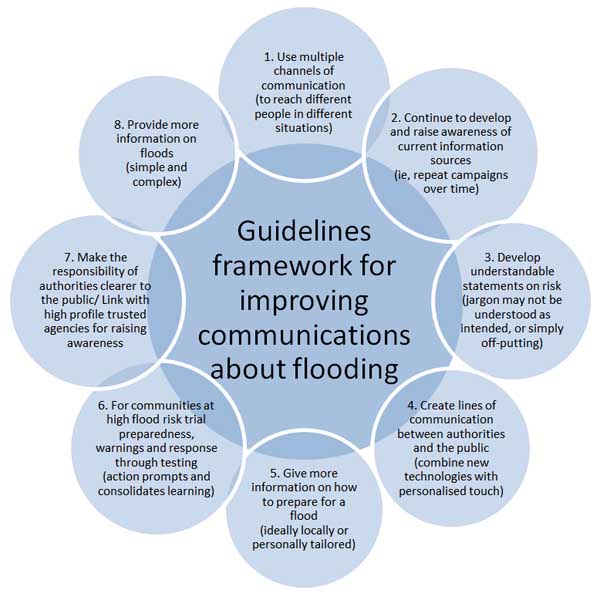

- We recommend a framework of eight inter-linked guidelines to aid the design of effective flood communications.

- Local context and past experiences should be combined with the guidelines, in order to identify useful approaches in a particular situation.

- Community engagement can directly support building community resilience and preparedness, as well as help outside agencies understand local perceptions that shape understanding of flood warnings.

Research Undertaken

This report is derived from a mixture of qualitative and quantitative approaches used to probe experiences and perceptions of flooding and flood communications in 11 at-risk communities, in four case study countries (Finland, Ireland, Italy, Scotland).

The communication of uncertainty and risk must be seen in the broader context of social, institutional, cultural and psychological influences on behaviour. Rather than assuming an information deficit model (that simply providing more or better information will always lead to more ‘rational’ responses) we based our research in the concept of ‘knowledge systems’, which highlights how different people can process, interpret and react to identical messages in quite different ways. Agencies and authorities may have assumptions about how messages are processed, but these may not match how the public understand and respond to messages. It is important to focus on the public’s perceptions, since they are the ultimate targets of communications about flood communications.

We used public focus group discussions to explore perceptions and experiences, and questionnaires tailored to each country, to survey trends and relationships in attributes of respondents living in at risk areas in 11 study sites. We used hundreds of questionnaires (in autumn-winter 2010). As a result of analysis of the questionnaire returns, we proposed a framework of guidelines for flood communication. This was further checked and tested in all the countries, through a mixture of focus groups, interview and surveys. This work was carried out for the ‘URFlood’ project .

Policy Implications

The work has implications for those involved in flood communications, including but not limited to SEPA and local authorities:

- The multiple organisations and agencies linked to flood communications could consider if existing roles and responsibilities could be shared and/or reconfigured so that various communications are perceived by the public to come from the most appropriate sources. Alternatively /in addition, a single outward-facing point of contact which links to further sources may assist.

- The public often appreciate personalised guidance on how to prepare for floods, and personal contact is a good way to reach individuals unaware of their flood risk. It would therefore be valuable to enabling practitioners to acquire skills in community engagement, or link with those that do.

- Automated flood warning messages (as via Floodline) are potentially a good way to communicate warnings, but limited by the number that chose to sign up. Policymakers should consider how to improve sign up, and/or consider ‘opt out’ not ‘opt in’ flood warning systems.

Authors

Kerry Waylen, The James Hutton Institute kerry.waylen@hutton.ac.uk

Andrew Cuthbert, The James Hutton Institute