Molecular Epidemiology: Fingerprinting the culprit

Published on 27 July 2010 in Sustainability and Communities

, Ecosystems and biodiversity

, Food, health and wellbeing

Introduction

When you buy eggs at the grocery store, do you buy organic, free-range, or Scottish, or maybe all or none of the above? Eggs are eggs, but not all eggs are the same. Different products suit different niches or markets. Similarly, not all sheep are the same and not all cows are the same. North Ronaldsay sheep have adapted to eating seaweed and could not survive in the hills. Blackface sheep are good hill sheep but could not survive on the shorelines of North Ronaldsay. Highland cattle thrive in the highlands, but they would not be much use as dairy cows. For British Friesian dairy cattle it is the other way around. Different breeds suit different niches or environments.

Key Points

What is true for animals, also applies to bacteria, parasites and viruses: within each species, we have different strains, and different strains suit different niches or environments.

Some strains of a species can be harmless, whilst other strains of the same species may be nasty pathogens that cause disease or even death. Some strains thrive in the outside environment or in crops, whereas other strains are much happier living in a warm-blooded host such as an animal or a human being.

To take that a step further: within a single host species, different strains may target different organs, say the respiratory tract versus the reproductive tract, or the udder versus the skin. Think of strains within pathogen species as breeds within animal species: it is a more refined subdivision, associated with specific traits.

Knowing the strain of a pathogen or the breed of animal tells us something about their behaviour and skills, which can be very useful. After all, who would bet on a bulldog racing against a greyhound?

Knowledge of pathogen strains is important in two major areas: disease causation and epidemiology.

Both knowledge areas contribute to disease prevention and control. Healthy animals are more productive than diseased animals and thus help us sustain food security whilst limiting the carbon footprint of food production. Control and prevention of disease also contribute to animal welfare and economic viability of our farms.

But it is not just animal health that is at stake: some pathogens affect people, through zoonotic (animal-to-people/people-to-animal) or food- and waterborne transmission. To prevent disease in humans, we need to know which pathogen strains of animals are dangerous to humans and how they spread. Examples would include methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), also known as “the superbug”; Cryptosporidium, the most common foodborne parasite in Scotland; and louping ill virus, a rare cause of encephalitis in people that is found in sheep, grouse and hares in the Scottish Highlands. When outbreaks of disease occur, it is important to trace its origin so that we can remove sources and stop further spread. For example, Cryptosporidium can come from humans, cattle farms, or contaminated water reservoirs. In some cases, farms have been seen as the source of water contamination, and restrictions on farming have been imposed. But what if the source of contamination is a rabbit, as happened in England in 2008? No number of farming restrictions could address that problem, only a thorough investigation to identify rabbits as a potential source.

Research Undertaken

Scientists at Moredun use a wide range of molecular, genomic and proteomic tools to investigate the diversity and spread of animal and human pathogens. Recent work, co-funded through the Scottish Government’s Centre of Excellence in Epidemiology, Population health and Infectious disease Control, EPIC, helped us identify specific strains of Pasteurella multocida that were associated with respiratory disease in cattle, haemorrhagic  septicaemia in cattle, and disease in other animals species.

septicaemia in cattle, and disease in other animals species.

Each niche has its own specific set of Pasteurella strains. Armed with such knowledge, Moredun Scientists can now proceed to develop disease models and vaccines that specifically target the relevant strains in each disease syndrome and host species, and reduce losses in growth rates of Scottish beef and dairy calves, and loss of life in cattle in tropical countries.

Similar studies are conducted on a wide range of other pathogens, e.g. on the bacteria E. coli and Streptococus uberis, the most common causes of mastitis in UK cattle;on Chlamydophila abortus, the most common cause of abortion in Scottish sheep; on bovine herpes virus 1, a cause of respiratory disease and abortion in beef cattle; and on Cryptosporidium species, which cause diarrhoea in calves and children.

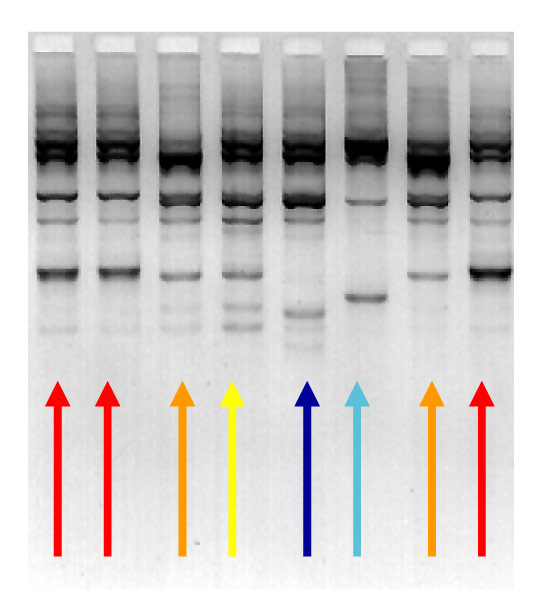

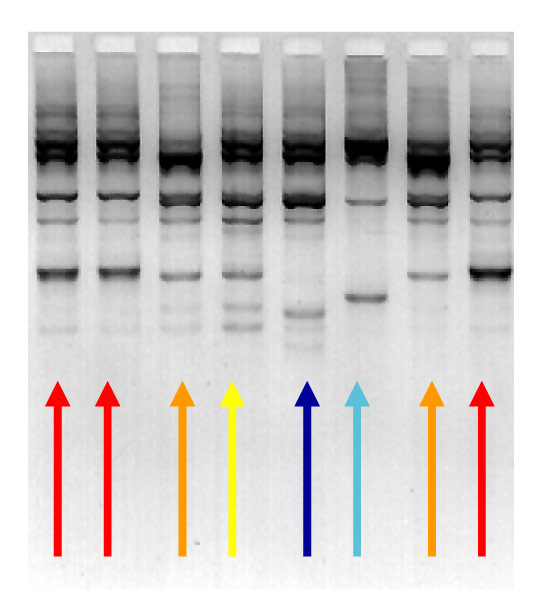

DNA fingerprinting techniques can identify which bacterial strains are the same, and different. The four different colours on this image show the four different strains of Streptococcus uberis present in the sample

Policy Implications

Molecular epidemiology research has important implications for development of disease control programmes, diagnostics and vaccines by targeting specific, relevant subsets of niche-adapted pathogens. Control of endemic diseases of livestock will promote welfare, decrease morbidity and mortality, and limit waste of greenhouse gases by animals with suboptimal production levels.

Molecular epidemiology research also contributes to effective management of zoonotic, food- and waterborne infections to safeguard animal and human health and promote the quality and safety of Scottish food and drink.

Author

Professor Ruth Zadoks ruth.zadoks@moredun.ac.uk

Topics

Sustainability and Communities

, Ecosystems and biodiversity

, Food, health and wellbeing

Comments or Questions

To take that a step further: within a single host species, different strains may target different organs, say the respiratory tract versus the reproductive tract, or the udder versus the skin. Think of strains within pathogen species as breeds within animal species: it is a more refined subdivision, associated with specific traits.

To take that a step further: within a single host species, different strains may target different organs, say the respiratory tract versus the reproductive tract, or the udder versus the skin. Think of strains within pathogen species as breeds within animal species: it is a more refined subdivision, associated with specific traits. septicaemia in cattle, and disease in other animals species.

septicaemia in cattle, and disease in other animals species.