Future disease threats to food crops - are we prepared?

Published on 18 October 2010 in Sustainability and Communities , Climate, water and energy , Ecosystems and biodiversity

Introduction

Monitoring crops for new threats provides an early warning of emerging problems affecting food production & quality.

Crops are continually affected by new pest weed and disease threats, and early recognition is important to understand their importance to Scottish food production. Long term changes in the climate may also lead to an increase in new outbreaks and also changes in the types of crops grown in Scotland. Maize is an example of a crop which is likely to increase in area, bringing with it new disease problems which can affect food quality.

When potatoes were first introduced into Europe, no major problems were documented. The fungal disease late blight struck Europe in the 1840s leading to poor harvests which resulted in famine in Ireland and Scotland. Starvation and mass emigration were the consequences of these famines.

Since the Corn Laws put high duties on imported grain, it was not the shortage of food per se, but a shortage of affordable food which caused so much misery. You can travel on destitution roads in Scotland which were built to provide work for people who could not afford to buy grain as a consequence.

Plant pathology was in its infancy at that time and although fungal diseases had been associated with poor harvests, they were not thought to be the primary cause of the damage, hence the lack of knowledge about this disease.

Key Points

- Thirty years of crop monitoring based on visual assessments provides a unique record of changes in crop health based on seasonality and long term changes in climate.

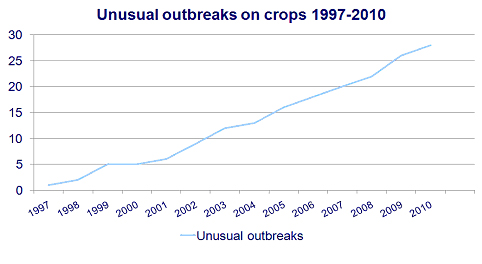

- Twenty eight unusual outbreaks have been reported since 1997 and are increasing as a consequence to changes in climate, pesticides and cropping practices.

- Molecular diagnostics help identify new threats and when integrated with visual; symptoms, spore trap and weather information, enhance our ability to understand the importance of new outbreaks.

- Early warning of new threats enables decisions to be made in good time on their potential impact on Scottish food production.

- A reduction in future monitoring will limit our ability to identify new threats and limit our ability to provide advice on their economic importance & control.

Research Undertaken

Crop health is the poor cousin to animal health when it comes to disease surveillance, but crops are essential both for animal and human nutrition. Crop diseases can cause low yields, but they may also produce toxins which have a direct effect on animal and human health.

Crop disease surveillance provides an early warning system which helps us focus on emerging threats which may have wide implications on the Scottish economy. Surveillance of crops throughout Scotland enables us to compare changes associated with seasonal weather patterns and also longer term changes in climate. In 2010, a new disease on wheat was identified, called tan spot. This disease causes economic losses in mainland Europe and USA. Where yield losses average 15%, but can be as high as 40%.

Why can’t disease surveillance be left to the industry? Growers manage crops on what they know. New disease outbreaks are ignored as experienced crop walkers do not recognise the disease threat. Once recognised, economic damage may already have occurred and there will be no information on how best to manage it leading to an increase in inappropriate pesticide use. Information on varietal resistance and fungicide activity will be limited.

New molecular technologies have enhanced our understanding of new disease threats and these techniques will play a future role in enhancing our ability to monitor for new threats. Spore traps have already helped our understanding of recent threats. When the barley disease ramularia leaf spot first appeared in 1989, little was known of the disease, the cause or its importance. It is now recognised in Scotland as a major disease threat to barley but information on its importance, biology and integrated management are now available. Future forecasting methods are also being investigated and likely to be implemented soon.

It is hard to judge where future threats will come from, but having an infrastructure of crop disease surveillance based on the systematic observation of crops spore trapping and weather data managed by experienced epidemiologists complemented by the use of new molecular technologies to understand these observed new threats will give time for policy decisions to be made to manage them.

Policy Implications

The EU Pesticide Directive 2009/128/EC will place greater emphasis on the need to effective surveillance, training. Cuts have already been implemented in the promotion of low pesticide input management, advice to the public and professional training of advisers. Directive 2000/29, the Plant Health Directive also highlights the need to identify threats early. If this aspect of current crop health activities is substantially curtailed from 2011 it risks putting back Scotland's ability to forecast new and evolving disease risks and advice to policy makers 150 years .Let us hope history does not repeat itself.

Author

Dr. Simon Oxley, SAC simon.oxley@sac.ac.uk

Topics

Sustainability and Communities , Climate, water and energy , Ecosystems and biodiversity