Parasites And Climate Change - Implications For Scottish livestock?

Published on 15 May 2009 in Sustainability and Communities , Climate, water and energy , Food, health and wellbeing

Introduction

There is a now a broad consensus amongst scientists that the global climate is changing. All available predictions would indicate that, over the next decade, the weather in the UK will feature greater extremes of climatic conditions, with a general trend towards drier, warmer summers and milder, wetter winters. These changes will obviously impact on the health and welfare of farmed animals, both directly and indirectly. Where a changing climate is likely to have a significant impact is in the transmission and epidemiology of livestock disease. There has been much publicity surrounding the incursion of "exotic" vector-borne diseases such as Bluetongue, however, endemic livestock diseases have been largely ignored.

Key Points

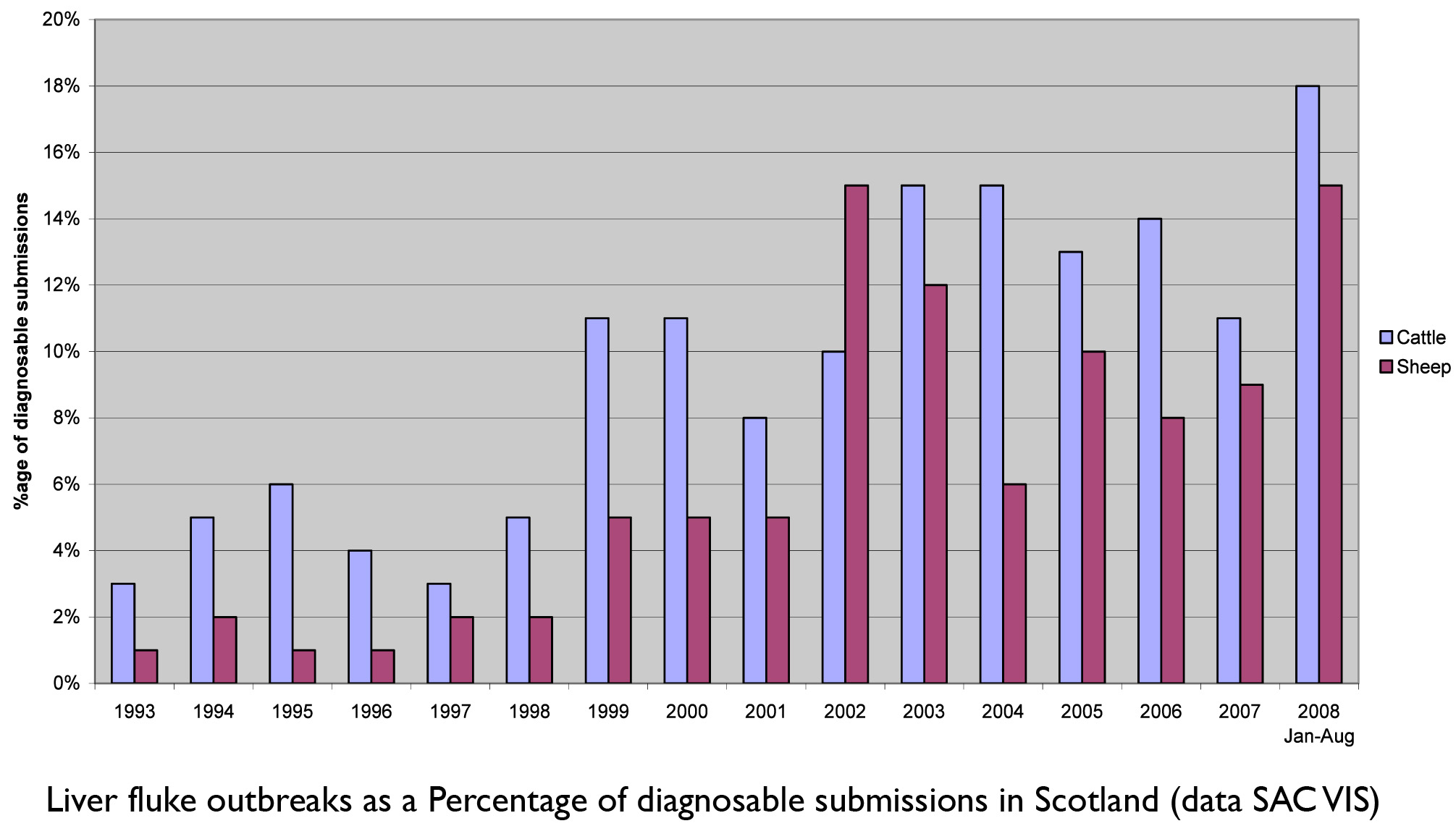

One of the key endemic diseases that may be affected by a changing climate is caused by liver fluke (a parasitic flatworm). This disease is a major economic burden to the livestock industry due to reduced productivity of infected animals and condemnation of fluke damaged livers at slaughter. Liver fluke disease is estimated to cost in excess of £50 million per year in Scotland alone.

Liver fluke and other parasitic worms are markedly affected by the weather and hence, over time, the climate, as they possess larval stages and, in the case of fluke, intermediate hosts that are free-living in the environment. The ability of some of these larval stages to over-winter on pasture or survive arrested within the host has the potential to alter the epidemiology of these infections and cause unexpected clinical disease.

Scientists at Moredun Research Institute in Edinburgh are investigating the effect that these, and other parasitic infections, are having on the health and productivity of UK livestock and trying to develop effective and sustainable control strategies for farmers.

Research Undertaken

- SNIFFER (The Scottish and Northern Ireland Forum for Environmental Research) have conducted a detailed study of the Scottish climate over the past 30 years. This report has revealed that the climate has changed significantly in that time. Temperature has increased (average, max and min); average precipitation has increased, with some extreme events; the number of frost days has fallen and the grazing season has been extended by up to 4 weeks in all regions. All of these factors conspire to extend the parasite season.

- Post-mortem surveillance data from Veterinary Investigation Diagnosis Analysis (VIDA) have been combined with clinical observations and case studies on farms to investigate the changing pattern of parasitic worm disease in Scottish livestock in relation to available regional climatic data.

- Moredun scientists have observed a significant increase in the prevalence of liver fluke infection in both sheep and cattle. There is also evidence of a west-to-east spread of disease and the seasonal pattern of infection has changed, such that acute fluke is being increasingly diagnosed in early spring.

- There has also been a similar increase in diagnoses of Parasitic Gastroenteritis (PGE) in both sheep and cattle. Heavy infestations of the brown stomach worm, Teladorsagia circumcincta, are now routinely diagnosed in spring when spring teladorsagiosis would have been considered extremely rare.

- There have also been increasing reports of outbreaks of the highly pathogenic, blood-feeding nematode, Haemonchus contortus, typically associated with more tropical climates but which now appears to be completing its life-cycle under UK conditions.

Policy Implications

The reliance of farmers and practitioners on a blueprint for parasite control in such a changing environment is unsustainable. Moredun scientists are working to develop improved, rapid and easy-to-use diagnostic tests to allow livestock producers to monitor the parasites present on their farms.

At present all available data have come from passive surveillance through diagnosable submissions to veterinary investigation (VI) centres. Active surveillance is required to monitor parasite populations on Scottish farms and, in future, accurate regional parasite forecasting would be beneficial in order to remain vigilant in a changing environment.

Moredun scientists are developing integrated parasite control strategies, including targeted selective treatments (TST) and vaccination, to provide sustainable alternatives and reduce the industry’s reliance on a dwindling supply of anthelmintic drugs.

There are a number of confounding factors, other than climate change, which could help explain the observed changes. These include the emergence and spread of anthelmintic (drug) resistance, the large-scale movement of animals (and their parasites) and the parasites’ inherent ability to adapt and change to exploit new opportunities such as those presented by climate change.

Author

Dr Philip Skuce philip.skuce@moredun.ac.uk

Topics

Sustainability and Communities , Climate, water and energy , Food, health and wellbeing