Potato Growers: Do You Know Your Enemy?

Published on 28 April 2010 in Sustainability and Communities

Introduction

The consequences of a failure to control the potato disease late blight are dramatic. In warm, wet conditions the pathogen Phytophthora infestans, can spread like wildfire and rapidly transform a healthy crop to a mass of rotting vegetation. Just such an epidemic in 1845 destroyed foliage and tubers and initiated the Irish Potato Famine. Such crop failures are, fortunately, not a feature of the modern potato industry.

A farmer’s knowledge of current management tools is the key to protecting the economically important Scottish seed and ware crop from late blight. Growers must however, keep pace with many changes within the industry, such as environmental protection legislation, produce assurance schemes, water use and climate change. Pest and pathogen evolution is also a vital consideration, as illustrated by a recent dramatic shift in the P. infestans population that has posed new challenges to the Scottish and UK industry.

All late blight outbreaks are started by P. infestans inoculum carried over from one season to the next and growers do their best to manage this by using certified healthy seed and destroying blight-infected plants growing from the previous year’s infected tubers in outgrade piles or in the field as ‘volunteer’ potato plants. This carry-over inoculum is a familiar concern to the industry but a potentially more serious threat is posed by the sexual stage of the pathogen that generates oospores that can survive in the soil for many years.

Oospores form when the two mating types of the pathogen, termed A1 and A2, meet during plant infection. Not only do these spores survive in the soil, acting as reservoirs of long-lived inoculum, but because they are the result of sexual recombination, new genetic variation is generated in the pathogen population. In the past, the A2 mating type was infrequent in the UK and consequently, the oospore threat was low. However, in 2005 signs of an increase in A2 caused concern that a more enduring source of infection in Scottish soils and an increasingly adaptable P. infestans population, able to rapidly overcome the two most useful management tools (fungicides and blight resistant cultivars), may emerge.

Key Points

- State-of-the-art genetic fingerprinting methods for P. infestans, comparable to those used in criminal forensics, have been developed at SCRI and proved vital in a Potato Council funded project to monitor and understand the evolving pathogen population.

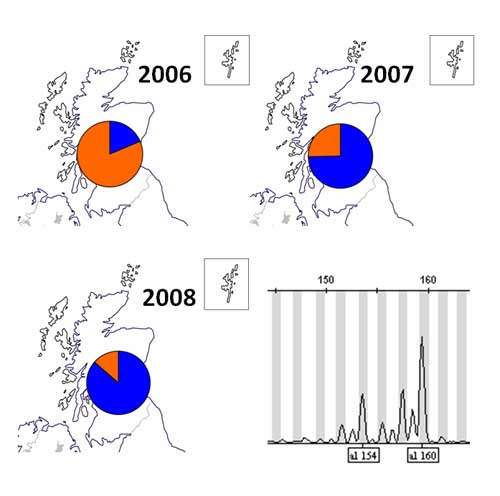

- A marked change in the Scottish pathogen population was documented with an increase in the A2 mating type from 25% in 2003 to 85% in 2008. A single clone of the pathogen (termed 13_A2), which was first noted in mainland Europe in 2004, accounted for this change.

- The new population (including 13_A2) was shown to be more aggressive, resistant to an important group of phenylamide fungicides and able to defeat previously useful sources of blight resistance. All these factors are altering the way potato farmers are managing potato blight in their crops. Use of phenylamide fungicides has, for example, declined.

- Knowledge exchanged with policy groups and stakeholders via many events in Scotland and a website with European partners. Key partnerships established with other leading scientists to investigate the drivers and implications of the population change in more detail.

Research Undertaken

Scientists at SCRI led a Potato Council-funded project, in partnership with other UK researchers, to examine the P. infestans population sampled from blight infected crops in unprecedented detail. Multiple samples were taken from over 1000 late blight infected potato crops from 2003 to 2009 and more than 4000 isolates of the pathogen from across Great Britain were fingerprinted using simple sequence repeat genetic markers (SSR). The data has shown a dramatic increase in the frequency of a single clonal A2 genotype of P. infestans in Scotland from 19% in 2003 to 86% in 2008.

This knowledge prompted a series of detailed experiments to examine the traits responsible for the success of this pathogen lineage. These studies confirmed that 13_A2 caused larger blight lesions which produced spores earlier than other P. infestans genotypes on a range of potato cultivars. This was supported by observations from agronomists that blight appeared to be more active in potato crops than in the past. The 13_A2 lineage was also able to overcome the blight resistance in nine of 11 plants in a standard reference set of, so called, single R-genes and overcome other valuable sources of resistance currently deployed by growers. Other studies have also confirmed 13_A2’s resistance to the previously important systemic phenylamide fungicides.

The results of this research have been presented to the key stakeholders such as growers, agronomists, potato breeders and representatives of the agrochemical industry where it has influenced decision making in both current disease management practices and the planning of future control strategies and crop breeding. The good news is that, to date, the threat of the oospore-borne inoculum is apparently low.

Figure 1: Increasing frequency of 13_A2 genotype (blue) of P. infestans over all other genotypes (orange) in Scotland. An example of the peaks representing SSR alleles used for fingerprinting the population is also shown.

Policy Implications

- Despite social and environmental pressures on reducing agrochemical use this change in pathogen population is increasing the need for growers to maintain a robust crop protection programme that will probably lead to an increase in fungicide usage.

- Breeding strategies must be responsive to such pest and pathogen evolution and novel approaches to breeding may be required to keep pace with the changes.

- A responsive multidisciplinary research programme in plant health is required that is able to detect new threats and inform the industry.

- An awareness of the threats of imported plant pathogens (particularly as a consequence of trade and climate change) pose to the Scottish potato industry should be maintained amongst the industry and the public.

Author

David Cooke, Alison Lees David.Cooke@scri.ac.uk

Topics

Sustainability and Communities