Encouraging land-manager contributions to protecting and enhancing the water environment

Published on 9 August 2011 in Climate, water and energy

Introduction

The Scottish Government recognises water as a key resource that is “vital to life, to Scotland's economy and to our environment”[1]. However, over the years many activities have had adverse impacts on both water quantity and quality.The Water Framework Directive (WFD) (2000/60/EC) sets out goals to control and monitor these impacts with aim of achieving ‘Good Ecological Status’. Multiple individuals across many sectors are involved in improving the water environment. This is because problems with the water environment arise from many different causes, from historic structures that affect bank morphology through to on-going pollution from septic tanks, forestry, urban development and agriculture. To improve the status of waters – particularly to reduce diffuse pollution (from many small cumulative sources) – action is needed from many, including land-managers.

Past approaches to managing the water environment have often focused on legislation but these have not always been effective, particularly for diffuse pollution. Incentivising land-managers to adopt measures for the water environment will be crucial for achieving improved Ecological Status. This is particularly true given the growing challenges posed by climate change and other future changes. This report outlines the key issues which can help or hinder land-managers adopting measures for the water environment. These issues may be common to measures for other pro-environmental behaviours (e.g. biodiversity conservation).

Key Points

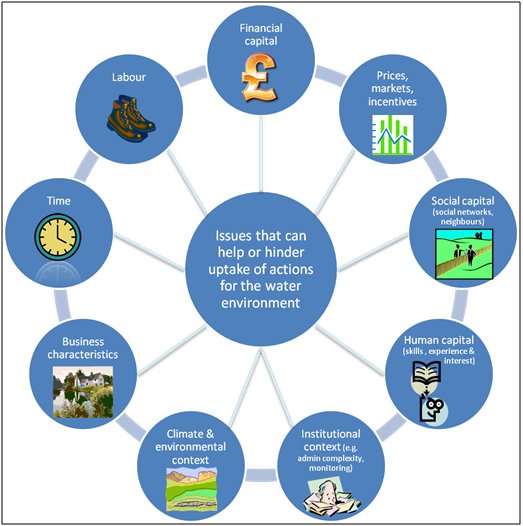

- There are nine key issues that can help or hinder uptake of measures for the water environment (see diagram on next page). Shortages of labour and time are common problems.

- Many of the issues are linked: lack of labour to carry out work can be linked to lack of time and money. Similarly, a lack of social networks can make it harder to learn about new practices, or funding schemes. However, these links mean some interventions can overcome several barriers at once: e.g. providing skilled personnel to help carry out a measure can overcome lack of time, labour and money.

- There are numerous rules and regulations, incentive schemes, and voluntary schemes. Being aware of all these schemes, let alone how they fit together, is challenging. The perceived complexity of this ‘paperwork’ is a significant deterrent.

- Land-managers sometimes feel unfairly targeted by rules and recommendations. Furthermore, some recommendations appear unworkable (particularly relating to dredging and ditch management) or even contradictory (e.g. can pesticides be used to control invasive species?).

- Future environmental and policy changes are expected (even if the nature of the changes are uncertain), but the key issues that help or hinder action are expected to remain consistent regardless of future conditions. The diagram of nine issues should therefore be useful in assessing adaptive capacity, as well as present uptake of actions.

Research Undertaken

We reviewed literature onpro-environmental behaviour, attitudes and adoption of pro-environmental measures by land-managers. After identifying potential issues in that review, we tested and refined these through discussion with land-managers in the River Dee catchment in North East Scotland in November 2010. There were 15 participants from throughout the catchment, whose interests included farming (both arable and livestock), horse livery, fisheries, forestry, and estate management. In December 2010 a similar workshop was held the Louros Catchment in Greece, to compare the issues raised in a very different catchment. Workshop discussion covered (1) current actions taken, (2) issues acting as barriers to adopting actions, (3) future changes expected and how these might affect actions. This work was funded as part of the ‘REFRESH’ project (Adaptive Strategies to Mitigate the Impacts of Climate Change on European Freshwater Ecosystems)[2] with support from the Scottish Government’s ‘Environment: Land Use and Rural Stewardship Programme’.

Policy Implications

The work has implications for water, agriculture and rural affairs, particularly Scottish Rural Development Programme (SRDP) funding policies, which need to consider:

- The shortage of labour and time. Supporting skilled labour may go some way to reducing the costs and time involved in carrying out some actions: for example, SRDP funding could be used to support apprenticeships and land based training (e.g. LANTRA), particularly combining productive and environmental land-management skills.

- Resource maintenance. Continuation of existing activities and maintenance of existing infrastructure can be as important as resourcing ‘new’ interventions. For example, once a riparian woodland has been planted, it will require sensitive management and/or coppicing to avoid over-shading the stream whilst maintaining bank structure. Funding sources such as SRDP need to accommodate this.

- Perceptions of fairness. Land-managers can sometimes feel unfairly singled out for attention, or an ‘easy target’ compared to some other sectors. When communicating about actions needed for the water environment, it may be useful to explicitly highlight if, and how, other sectors are also expected to take complementary actions.

- Desire for context-specific advice and incentives. If a trusted source can provide context-specific expertise (i.e. tailored to a particular area or business), this could overcome many problems perceived with interpreting and resourcing multiple rules and guidelines, especially for those that appear confusing or even contradictory. There is a role here for Scotland's Environmental and Rural Services (SEARS) partnership.

- Partnership working, especially by existing forums and organisations. Such partnerships can provide a trusted forum for learning, and also help tackle problems that require coordinated action (e.g. removing invasive species). Given the nature of expected changes (unpredictable but including more extreme environmental events), this may become more important in future. There is a role here for SRDP (including LEADER) funding.

[1] http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Topics/Environment/Water

[2]REFRESH is a large scale integrated project (2010 – 2014) funded under the EU FP7 - see www.refresh.ucl.ac.uk

Author

Kerry Waylen, Kirsty Blackstock, Susan Cooksley and Jill Dunglinson kerry.waylen@hutton.ac.uk