Diet and Deprivation

Published on 21 October 2010 in Food, health and wellbeing

Introduction

People in poorer areas not only die younger, but they will also spend more of their shorter lives with a disability. Reducing health inequalities is a matter of social justice but it is also vital to achieving the Scottish Government’s overall purpose of sustainable economic growth (1). The Chief Medical Officer for Scotland has highlighted the “Scottish Effect”, whereby the well documented link between poor health and social status is even more pronounced in Scotland than the rest of the UK. Despite producing fantastic food Scotland has one of the poorest diets and diet-related health records in the developed world. It is estimated that 70,000 premature deaths could be avoided each year in the UK if our diet met existing nutritional guidelines (2). Many UK health policies designed to tackle the problem of inequality are aimed at improvement of the diet in poorer socio-economic groups but these have met with very limited success.

Key Points

- Social disadvantage in the UK persists throughout life and across the generations and is proving increasingly difficult to overcome. Narrowing the gap in health inequalities is now one of the main health improvement challenges in Scotland.

- Diet is acknowledged to be an important determinant of health but its relationship to socio-economic class and deprivation related ill-health is poorly understood.

- Pregnancy is acknowledged as a key life stage, critical for both the current and the next generation. Deprivation results in poor pregnancy outcome and this in turn is associated with lower educational attainment in the offspring and disadvantage throughout life; a vicious cycle.

- Over a quarter of low birth weight is thought to be attributable to social inequalities and there is little evidence that the situation is improving.

- There is a need to understand more about the nature of the diet of deprived and vulnerable groups in the population and how it influences health and the propagation of disadvantage.

Research Undertaken

We studied 1,461 singleton pregnancies; mothers and newborns in Aberdeen (3). We assessed diet and measured nutrient status in mothers and newborns. We collected additional information on alcohol use, supplements, smoking, etc. We determined socio-economic status assessed by Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD).

Poor diet contributed to inequalities in pregnancy outcomes even after adjustment for the level of deprivation. We identified specific dietary components associated with these poor outcomes. The way such diets interacted with other factors associated with deprivation to influence outcomes was complex. The most deprived women were subject to multiple disadvantage in many areas. For example, women are advised to take folic acid supplements to reduce the risk of neural tube defect yet folic acid use in the critical peri-conceptual period is lowest in precisely those women who would benefit most because of a poor general diet and low intake of natural folates. Improving the diet and nutrient intake of disadvantaged women of childbearing age may help to break the vicious cycle of deprivation by improving pregnancy outcome.

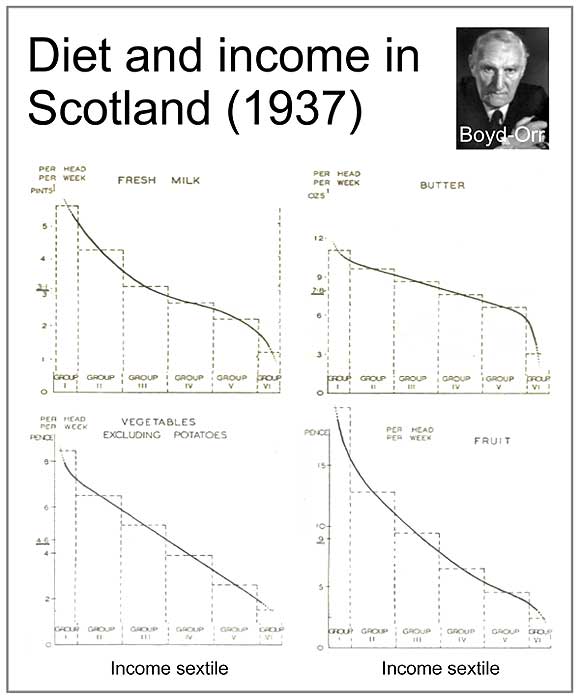

This analysis is relevant to improving pregnancy outcomes in the most disadvantaged in society but it also has wider implications. Lord Boyd-Orr first described over 70 years ago how the most deprived in society have a poor diet. We find the same thing today but the nature of the ‘deprived’ diet has changed markedly. The more affluent in society tend to consume traditional foods but the increasing artificiality of low cost foods is resulting in the consumption of diets in the more disadvanatged which are adequate in energy but with low intakes of specific nutrients and unusual nutrient combinations. We need to understand more about how these ‘artificial’ diets affect health. Our analysis also suggests that the potential health gains associated with dietary improvement are not just confined to the most deprived but extend over a significant proportion of the population. By breaking deprivation down into deciles we can see that for many dietary components the problem of deprivation related poor diet extends to at least half the population.

Policy Implications

Improving the diet and nutrient intake of disadvantaged women of childbearing age may help to improve pregnancy outcome and break the trans-generational propagation of deprivation.

Identifying the precise dietary patterns associated with deprivation in contemporary society, and the specific sectors of the population affected, will help in the development of more targeted and effective health improvement strategies related to diet.

Our work on diet in pregnancy has already contributed to the development of policy on folic acid through the work of the Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (4).

1. Health Inequalities Task Force. Equally Well, report of the ministerial task force on health inequalities. 2008. Edinburgh, Scottish Government.

2. The Food Research Group. UK Cross-Government Strategy for Food Research and Innovation. 2010. London, Government Office for Science.

3. Haggarty, P. et al. Diet and deprivation in pregnancy. Br. J Nutr. 102, 1487-1497 (2009).

4. Folate and Health, A report of the Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition. 2006. TSO, London.

Graph highlighting the change in intake of nutrients and food groups with increasing level of deprivation.

.jpg)

Change in intake of food groups with increasing degree of poverty (Boyd-Orr 1937).

Author

Dr. Paul Haggarty p.haggarty@abdn.ac.uk