Peatland Restoration may aid the Ecosystem Service of Regulating Pests and Disease

Published on 19 February 2014 in Sustainability and Communities , Food, health and wellbeing

Introduction

Peatlands that are drained and damaged emit carbon into the atmosphere, contributing to climate warming, whereas undamaged, good quality peatlands are highly important carbon sinks. Therefore, climate change mitigation policies are helping to drive large-scale projects to restore 6000 ha of damaged peatlands in Scotland back to good quality blanket bog.

Because good quality blanket bogs act like giant sponges, restoring peatlands is also likely to aid the important ecosystem services of flood mitigation and water quality. Large areas of good quality blanket bog are also of vital importance for maintaining and enhancing Scotland-wide biodiversity, as a small number of very rare species of conservation importance rely on blanket bogs.

Intact peatlands are therefore of diverse and important value; however, an ecosystem service as yet unconsidered for peatlands is that of “Regulating pests and disease”.

Key Points

Ixodes ricinus (sheep) ticks are the most ubiquitous and important vector of disease-causing pathogens in Europe.

These ticks transmit a range of pathogens, including Borrelia burgdorfi, the agent of Lyme borreliosis, a human disease which is currently increasing rapidly in Scotland; and louping ill virus, which kills sheep and red grouse, animals crucial to the economic sustainability of rural Scotland.

How will such a major land use change, restoring 6000 ha of land back to blanket bog, affect ticks and disease risk?

In this study, I tested the impact of restoring afforested peatlands on tick populations.

Research Undertaken

Tick, vegetation and deer dung surveys were conducted at Forsinard Flows RSPB reserve in Sutherland. The RSPB are currently felling large patches of conifer plantation in order to restore the land back to the original blanket bog. There is therefore a mosaic of large areas of extant forestry, restoration felling areas (felled brash of various ages, from three to 13 years old) and undamaged original blanket bog (photograph above).

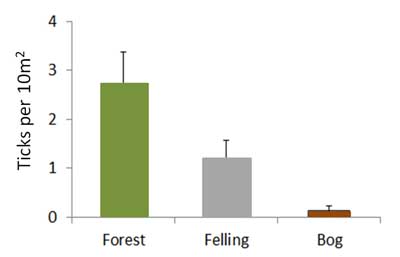

Surveys revealed a dramatic decline in ticks throughout the restoration process. Ticks were highly abundant in forestry, almost absent from blanket bog and had intermediate numbers in restoration felling areas (F2,1007=163, P<0.0001) (Figure 1 below), and newly felled areas had more ticks than areas felled 13 years previously (F1,558=31, P<0.0001). Therefore, there was a continuous decline in ticks throughout the restoration process.

What is the mechanism for this virtual eradication of ticks? Deer dung surveys revealed that deer, which are the principle host for ticks in Scotland, spent very little time on blanket bog, preferring forest and felled areas (F2,1012=27, P<0.0001). Furthermore, the forestry plantations have a dense canopy cover, creating a mild, humid micro-climate excellent for tick survival. Therefore, deer habitat preferences coupled with the micro-climate created by forestry, explain why ticks decline from forestry, though felling areas, to blanket bog.

Figure 1: Mean nymphal tick counts on 10 m x 1 m transects in forestry plantation, restoration felling areas and undamaged blanket bog at Forsinard Flows RSPB reserve. Standard error bars are shown.

This research was funded by the Scottish Government. Sincere thanks to the RSPB, Norrie Russell and David Ferguson. These results are published in the journal Journal of Applied Ecology: Gilbert, L. 2013. Can restoration of afforested peatland regulate pests and disease? Journal of Applied Ecology 50, 1226-1233. (doi: 10.1111/1365-2664.12141)

Policy Implications

- These results have strong implications for disease risk, which will be much reduced where ticks are rare. Peatland restoration therefore has an additional benefit: that of regulating pests and disease.

- The benefit will be enhanced where procedures speed up the restoration process or where deer management takes place.

Author

Dr Lucy Gilbert, James Hutton Institute lucy.gilbert@hutton.ac.uk

Topics

Sustainability and Communities , Food, health and wellbeing