Ticks And Tick-Borne Diseases In A Changing World

Published on 5 November 2009 in Food, health and wellbeing

Introduction

Vector-borne diseases are of major health and economic importance. In the UK the primary arthropod vectors of zoonotic pathogens are ticks, which transmit several zoonotic pathogens of importance to human and animal health and welfare, with consequences to rural economies and livelihoods.

Recent studies have shown that ticks and tick-borne diseases are increasing in the UK. Alongside these increases, woodland and forest cover is changing, with big increases in forestry planned. Numbers of livestock and wild herbivores are also changing, for example both red and roe deer, key hosts of ticks, are increasing in abundance and distribution. If disease risk is to be managed, we need to know how these environmental changes and how potential management methods will affect ticks.

Key Points

Key tick-borne pathogens of importance in Scotland include Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, the agent of Lyme disease in humans, and louping ill virus that causes mortality in red grouse and sheep.

Ticks and louping ill are increasing on Scottish grouse moors and reported cases of Lyme disease in humans in Scotland are currently increasing rapidly. One hypothesis is that the increases in woodland and deer numbers may be affecting tick numbers and, consequently, disease incidence.

Research Undertaken

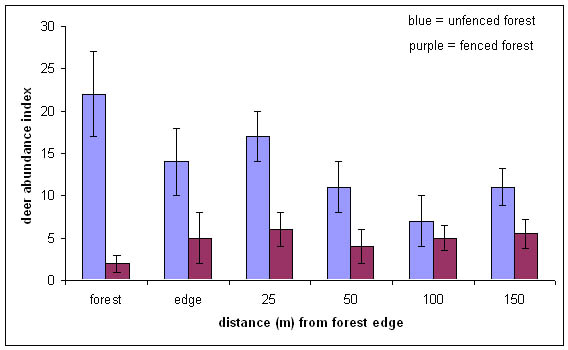

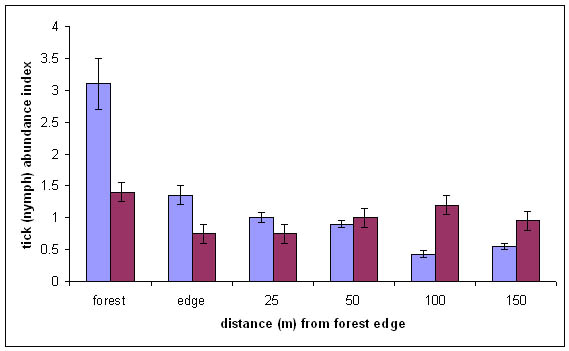

Since deer move between woodland and moorland, it is possible that ticks are spread onto moorland by deer. Therefore, one potential management tool could be to fence woodlands to restrict movement of deer between the two habitats. We tested the effects of deer abundance, deer movement between habitats and fencing on tick abundance in upper Deeside, Grampian. We surveyed ticks and deer (using dung counts) in forests and at different distances away from the forest edge onto the moorland. We compared forests that were fenced to exclude deer with those that were unfenced where deer could move freely between habitats.

We found that areas with more deer also had more ticks and that forests had higher tick density than did moorland. We found that forests that were fenced had fewer deer (as one might expect!) and, importantly, significantly fewer ticks than unfenced forests. This effect of more ticks in unfenced forests also meant more ticks on the adjacent moorland, but only for a distance of 25m away from the edge of the forest. Beyond 25m into the moorland, forest fencing had no effect on moorland tick abundance.

Our findings support our hypothesis that increases in woodland and deer numbers will increase the abundance of ticks. However, we do not yet know if this will cause a rise in disease incidence. This study also suggests that fencing forests could be a useful management tool to reduce ticks (and potentially Lyme disease risk) in woodlands. However, we failed to find sufficient evidence that fencing forests will successfully reduce tick populations on adjacent moorland, except close to the forest edge.

Policy Implications

Health Protection Scotland data indicate that reported cases of Lyme disease have increased 25-fold in the last ten years. This clearly has implications for our health and wellbeing, cost to the NHS, and has the potential to affect rural economies in Lyme disease “hot-spots”. In parts of Scotland the grouse shooting industry can be crucial to livelihoods and the local economy; however, ticks and louping ill virus are perceived by grouse moor managers to be one of the most important current issues in the Scottish uplands and one of the biggest threats to their livelihoods.

This research provides important pointers to inform policy about which places are likely to be most at risk from ticks and potential disease, in terms of habitat type and deer abundance. It can also inform management practice in terms of the use of fencing, managing deer numbers and placing of woodlands with respect to the effects on ticks. However, in areas where Capercaillie and Black Grouse occur fencing woodland may not be acceptable and reduction in deer numbers may be the only practical alternative approach. We are currently extending this work into mathematical models to predict the effects of deer movements, deer abundance, the use of fencing and forest/moorland mosaics on louping ill virus on adjacent grouse moors.

Author

Dr. Lucy Gilbert l.gilbert@macaulay.ac.uk